Governance.

Results Overview

Governance.

The governance factor was assessed by looking at four criteria

1. Governance structure and mission

Average country score: 77

Scores for this component far exceeded those of any of the other three components. This result while positive isn’t necessarily reason to celebrate as the component really measures the “table stakes” of governance disclosures:

- 96% of all funds provided an overview of their governance structure;

- 93% of all funds named all their directors; and

- 95% also listed all sub-committees subordinate to their main board.

Scores in other areas were not quite as positive with some basic disclosures far from universal:

- Only 69% of all funds disclosed a clear mission statement;

- More than 20% of funds did not disclose how or by whom board members were selected;

- Despite the almost universal disclosure of sub-committee names, only 77% of funds provided details on each committee’s responsibilities with only 76% listing the membership of each committee; and

- Only 36% disclosed board policies around conflicts of interest and how they are dealt with.

Many disclosures were commendable but there are some areas that need improvement including:

- While most funds did disclose their governance structure, many disclosures were somewhat vague and seemed to assume that readers would be familiar with governance norms of the country. This seemed particularly true in countries where fund governance structure is quite tightly regulated.

- Board member selection/election disclosures were often quite vague and rarely talked about timing of past and/or future elections/selections. In addition, committee member start and end dates were often not disclosed. In combination, it is hard for stakeholders to gauge how frequently the board turns over and evolves.

Questions relating to governance structure and mission

- Is the overall governance structure for the fund outlined?

- Does the fund have a clear mission statement identified as such?

- Are all sub-committees listed?

- Are the parties responsible and methods for selecting the board member outlined?

- Are all the members of the board of directors named and listed?

- Are the sub committees that each member sits on documented?

- Is the start date and each members term listed?

- Are the oversight responsibilities of the board and each sub committee available for view, or at least a detailed summary?

- Is the board’s conflict of interest policy detailed as well as how real or apparent conflicts are dealt with?

- Are the fund’s processes for monitoring portfolio companies, including proxy voting policies disclosed?

2. Board competencies and qualifications

Average country score: 35

Disclosure of board competencies and qualifications was disappointing with only Canada scoring above 80. Australia and the United Kingdom were the only other countries to score 60 or higher.

Disclosure of board member experience and relevant qualifications was the only area in which most funds reviewed received a positive score. At 55%, this result is still very disappointing for what should be a basic disclosure. It should be noted that simply stating a board member’s education was not enough to garner a positive score. At the very least disclosure of career achievements in addition to education is a minimum.

Other notable areas included:

- Only 36% of funds made mention of board effectiveness reviews, with even fewer (21%) making mention of continuing education endeavors for board members; and

- The number of board and subcommittee meetings was disclosed by only 40% of funds. 90% of funds that did disclose the number of meetings, also disclosed board member attendance for the full board, but only two thirds did so for each sub-committee.

It goes without saying that there is ample room for organisations to improve including:

- The use of plain language to describe the skills and qualifications of board members and how they are relevant to the oversight of the fund;

- Demonstrating a commitment to having a knowledgeable, well qualified board by disclosing continuing education initiatives and board review processes; and

- Holding board members accountable by disclosing board member attendance at both the full board and for any sub-committees.

Questions relating to board competencies and qualification

- Are board members experience and relevant qualifications listed?

- Are the desired competencies of the board of directors listed?

- Are actual board member competencies contrasted against desired competencies?

- Are changes to the governance process and/or structure (if any) in the prior year discussed?

- Are continuing education policies for board members documented?

- Are board effectiveness reviews discussed?

- Are the number of meetings of the the board and each subcommittee documented?

- Is the attendance record of each member of the board recorded?

- Is the attendance record of each member of a sub committee documented?

3. Compensation, HR and organisation

Average country score: 44

Disclosure of compensation, human resource and organisational information showed the greatest amount of variability across countries of any component. Four countries had scores of 75 or above. Conversely there were also four countries that scored less than 15.

There were several causes for the wide range in scores, particularly salary disclosure:

- In six countries, all five funds disclosed board member compensation, in four others, none of the five funds did; and

- In two countries, all five funds disclosed total compensation for the CEO and their top two reports, in seven others, none of the five funds disclosed management salary information.

While it was evident that country norms likely played a role in the decision on whether to disclose remuneration, some findings aren’t as easy to explain:

- While only 31% of funds chose to disclose management remuneration, 50% disclosed their processes for determining management remuneration, at least at a high level. Conversely, while 57% of funds disclosed board compensation, only 39% said anything about how board compensation was determined.

- Just over half of the funds made disclosures about employee diversity programs. In 14 of 15 countries, at least one fund reported on their diversity programs. The only country that didn’t was, somewhat surprisingly, the Netherlands.

Recognising that disclosure of actual remuneration may be a difficult sell in countries where it is not required, there are still several areas where compensation, HR and organisation disclosures could be improved:

- Many disclosures on board compensation philosophy were quite vague. It would be good to see more disclosures around time commitments and peer groups used to determine board compensation.

- Disclosures around management compensation philosophy are more insightful if they provide clear details on how variable compensation is aligned with stakeholder outcomes. Better still if the relevant organisational results are disclosed along with actual management remuneration to demonstrate that compensation philosophy is being followed in practice.

Questions relating to compensation, HR and organisation

- Are processes and/or philosophies for determining compensation for management disclosed?

- Are processes and/or philosophies for determining compensation for the board disclosed?

- Is compensation for board members shown?

- Are the names and titles of the CEO and top four direct reports available?

- Is total compensation for the CEO and the two next highest comped management members disclosed individually?

- Is variable compensation for the CEO and the two next highest comped management members disclosed separately?

- Is total staff compensation disclosed?

- Is the total organisational headcount disclosed?

- Are the fund’s employment diversity policies listed?

- Are specific diversity targets listed?

4. Organisational strategy

Average country score: 26

This component had the lowest weighting and fewest items of the four components. Disclosure of organisational strategy, use of third parties and high level investment philosophy are surely useful information for stakeholders, but perhaps not as critical as items covered in the previous components. This is fortunate as scores were consistently poor both within and across countries with only Canada (76) and the Netherlands (53) scoring above 50.

What should funds do better:

- There needs to be more discussions on corporate strategy. Much like traditional corporations in other industries, asset owners’ corporate strategy extends beyond their core mission. Stakeholders deserve some insight. Examples could include plans to in-source certain functions, development of a new website or member portal, or perhaps human resource initiatives. A review of progress in the prior year is good, disclosure of strategies for the following 3-5 years, even better.

- It would be insightful to know more about high level investment philosophy, including: preferences for active versus passive management and internalisation of asset management functions.

Questions relating to organisational strategy

- Is the fund’s mix of/philosophy for active/passive strategies disclosed?

- Is the fund’s mix of/philosophy for internal/external investment management disclosed?

- Is the amount spent on external consultants disclosed?

- Are the fund’s corporate goals discussed for the previous year?

- Are the fund’s corporate goals for the following year discussed?

To view all questions to each component, visit the Methodology page here.

Average country score

Highest score

Governance questions asked

Overall Results Governance.

Overall Ranking

1.Canada

2.Australia

3.Sweden

4.Denmark

5.United Kingdom

6.South Africa

7.Finland

8.The Netherlands

9.Chile

10.Norway

11.United States

12.Brazil

13.Switzerland

14.Japan

15.Mexico

“If you don’t know where you are going, any road will get you there.”

Lewis Carroll in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

Governance.

Organisations were scored based on 34 questions across four components. The average country score was 53 out of a possible 100. The biggest Canadian public funds collectively have a global reputation for superior performance, and governance excellence is often cited as a key driver (the Maple Model). The fact that the five largest Canadian funds had the highest average score for the Governance and Organisation factor also supports their collective reputation for governance excellence.

Governance and Organisation scores were more closely correlated with overall score than any of the other factors. Perhaps as good governance produces positive results, it creates greater incentive (or perhaps less disincentive) to be transparent with stakeholders.

The assessment of governance and organisation disclosures included 34 total questions organised across the four components outlined below. Annual reports usually contained much of the information with much of that information mirrored or supplemented on websites. Occasionally, some disclosures were found in other documents such as: codes of ethics, corporate governance/stewardship guidelines; and investment policy statements.

1. Governance structure and mission (40% of governance and organisation factor score)

Effective stewardship of large pools of assets requires a robust governance structure with a clearly articulated mission. While assessing the quality of the governance structures in place is beyond the scope of the project, certain information is required for stakeholders to do any form of appraisal. Is the overall governance framework outlined including all committees and subcommittees responsible for overseeing management? Are the respective responsibilities of these bodies clearly articulated? Are the individuals who serve on these bodies identified along with how long they have served in their roles?

2. Board competencies and qualifications (20% of governance and organisation factor score)

A governance structure is only as effective as the combined skills and experiences of the individuals involved. Desired skills and competencies should be identified and disclosed, as should the actual skills and competencies of current directors and committee members. Governance structures and processes should evolve to meet changing needs. Disclosure of changes to process and structures, board effectiveness reviews, and continuing education endeavors signal an organization with a governance structure that is dynamic and evolving. Unlike the ongoing nature of management, boards and committees convene only a finite number of times per year. The number of board and committee meetings along with member attendance should be disclosed.

3. Compensation, HR and organisation (25% of governance and organisation factor score)

Effective compensation policies should allow the attraction of skilled individuals and help drive and reward desirable behaviors. The processes and philosophies on how compensation is determined for both the board and senior management should be disclosed. And actual compensation disclosures, for the board, the CEO, and the management team is a demonstration that these processes are being followed. Total staff headcount and compensation lend insights into the structure of an organisation. Statements of diversity demonstrate that an organization is focused on all aspects of employee wellbeing.

4. Organisational strategy (15% of governance and organisation factor score)

Disclosing overall organisational strategy beyond simple investment strategy, both for the past year as well as the future, demonstrates an integrated approach to management and allows stakeholders a more fulsome view

Best Practices

What – The skills and competencies possessed by the board should be disclosed and contrasted against desired skills and competencies.

Why – For a board of directors/trustees to effectively discharge their responsibilities, they need to possess, as a group, certain skills and competencies. This is true even for lay boards who rely extensively on third-party expertise. At a minimum, directors must have enough skill to accurately synthesise information provided to them by their advisors. It is important for organisations to provide stakeholders enough information to accurately assess the skills and competencies of the board:

- Disclosure of the actual skills and qualifications of board members is required for stakeholders to assess if the board is qualified to effectively discharge their duties;

- Disclosure of the desired skills and competencies provides stakeholders with a framework with which to conduct their assessment; and

An explicit comparison of desired competencies with those of the current board provides full transparency on how well reality aligns with desires.

How – Skills and competencies should be clearly disclosed individually for each director.

- While educational achievements are no doubt relevant, they are far from enough information for stakeholders. An MBA granted 30 years prior is hardly concrete evidence that one possesses the skills necessary to guide a multi-billion-dollar fund.

- Evidence of other senior management positions and/or board appointments are more helpful in assessing the level of skill possessed.

- Ideally skills and competencies are listed in plain language that relate the skills and competencies to those required in overseeing the retirement fund. Unfortunately, disclosures of this sort are exceedingly rare.

Where – The skills and competencies of the board of a fund is critical for its effective function over the long term. Ideally this information will be disclosed in the governance section of the fund’s website where it can be kept up to date due to changes to the board that happen during the year.

- Many websites provide the ability to click through to detailed information on each individual board member.

- Fund websites should also provide an overview of how the board is selected. This is an excellent place to list desired competencies, or if conciseness is desired, a link to where the desired competencies can be viewed.

Ideally the information would also be available in the fund’s annual report. However, a clear and concise 50-page annual report is almost always superior to a 350-page data dump. In absence of including the information in the annual report, funds should note the existence of this information, preferably with a direct hyperlink to the relevant document.

Best practice examples:

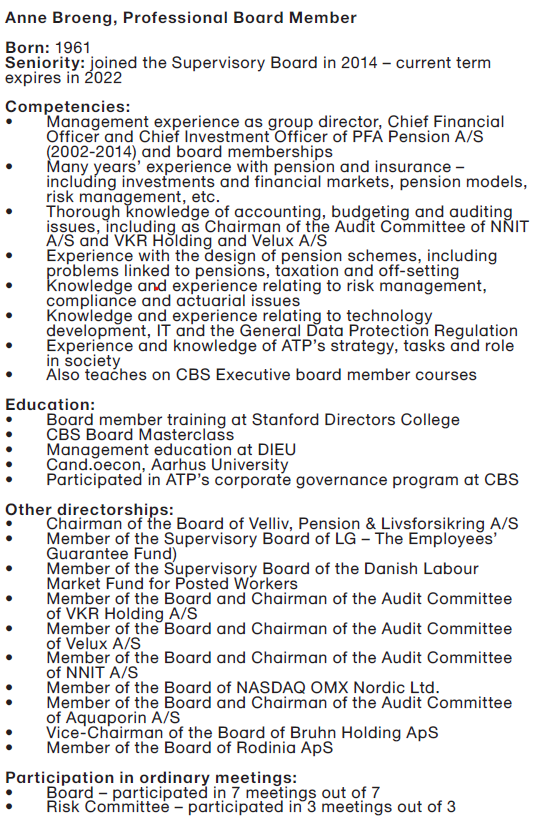

ATP

An example from Danish fund ATP’s 2019 annual report (page 138), outlines competencies in plain language in a way that is easily relatable to their current board position. This information is supplemented below with the board members’ educational qualifications and other directorships providing a full picture of the skills possessed by each board member.

Ideally the desired skills and competencies of directors will be identified ex ante to avoid the fitting of desires to the current reality.

- Disclosure helps stakeholders to assess if there are gaps in the skills and competencies possessed by the current directors.

- Without a complete list of desired skills and competencies, stakeholders must conduct their own assessment the skills they feel are required.

Source: ATP’s Annual Report 2019 (page 138)

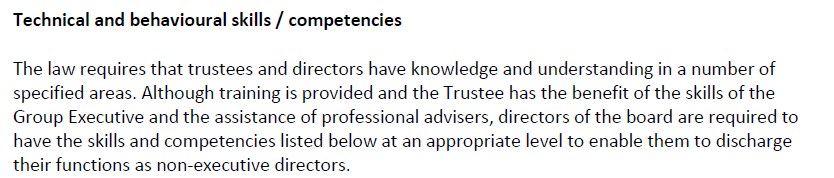

Universities Superannuation Scheme

Universities Superannuation Scheme, a UK fund, publishes a document titled Corporate Governance Framework Policy on its website. Pages 67 – 68 includes full job descriptions for prospective board members, an excerpt of which is shown below. These job descriptions provide full clarity as to the type of skills and competencies desired. It would be even better if they were to have this summary as part of the governance disclosure in their annual report.

It is even better if the organisation takes it upon itself to disclose its assessment of the actual situation, providing stakeholders with a clear and honest appraisal of the actual board skills and competencies versus those that are desired.

Source: Universities Superannuation Scheme Corporate Governance Framework Policy (pages 67 – 68)

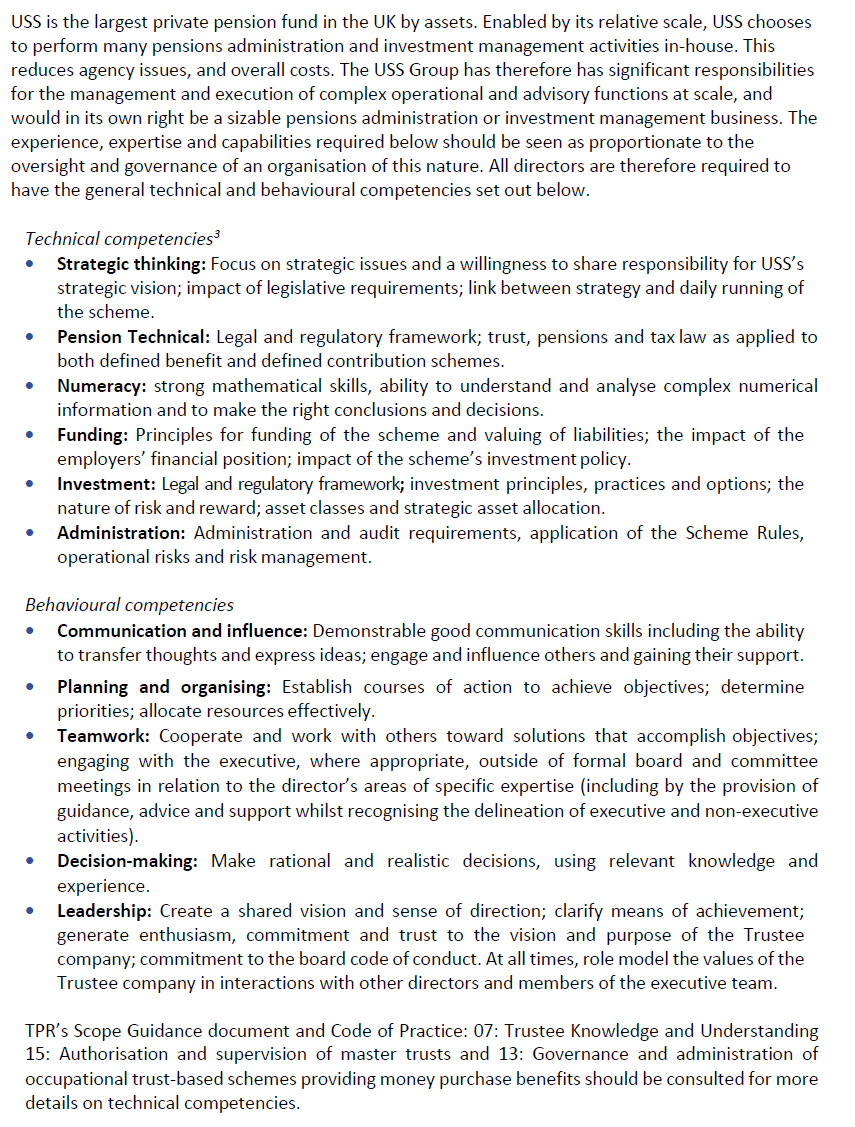

QSuper

The third example comes from Australian superannuation fund QSuper. It is excerpted from page 5 of a document available on its website which the fund produces annually to demonstrate its compliance with the Australian Institute of Superannuation Trustees’ governance code.

The desired board competencies can be easily viewed along the horizontal access. The chart clearly shows QSuper’s view of not only the presence of these competencies among its board members, but also their relative skills in each. It’s unfortunate that this very informative chart is not included in their annual report where it would be more likely to be seen by stakeholders.

Source: QSuper’s Governance – Compliance with Australian Institute of Superannuation Trustees’ Governance code 2020 (page 5)